Photographer Sebastião Salgado on his visual poetry

Jul 16, 2025

One of the greatest photographers of our time, Sebastião Salgado made a habit of deeply immersing himself in the lives and landscapes he documented. Dionne Bel shares his story

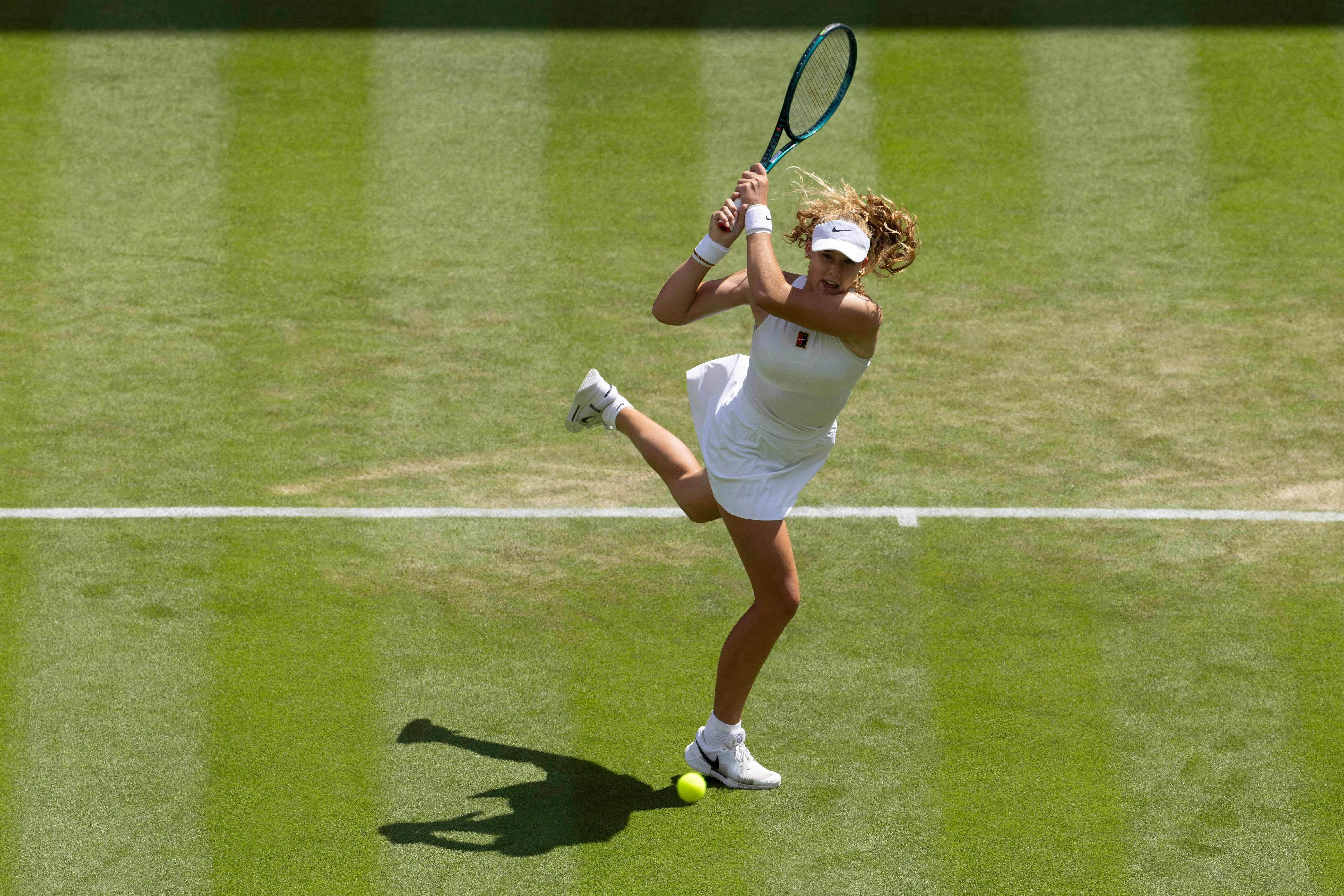

With his striking black-and-white images, Franco-Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado spent the past five decades chronicling humanity with a rare depth of compassion and clarity. Trained as an economist, Salgado didn’t pick up a camera until the age of 29 – but once he did, there was no turning back. His lens has borne witness to workers in vast mines, families displaced by conflict, the raw beauty of untouched landscapes and the lush, vanishing rainforests of the Amazon. Each one spanning years, his long-term projects – Other Americas, Workers, Exodus, Genesis and Amazônia – reveal a gift for elevating documentary photography to visual epic poetry.

For Salgado, who died unexpectedly in late May, his work wasn’t just about observation – it was about engagement. Alongside his wife and creative collaborator, Lélia Wanick Salgado, he co-founded Instituto Terra, a reforestation project that has restored degraded land in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest into a thriving ecosystem. As part of its Year of Brazil, Les Franciscaines cultural centre in Deauville, France, staged a retrospective of Salgado’s major series, organised with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. It was a rare chance to trace the arc of a photographer who has captured the fragile splendour of our planet and the complexities of human existence, bringing light to the dignity, struggle and resilience of people often overlooked by mainstream narratives.

We spoke to Salgado before the exhibition opened.

How would you describe your exhibition at Les Franciscaines?

When we arrived there, we toured the exhibition. And for me, it was like taking a tour of my life. I had the privilege to have been able to go to all these places. That’s the power of the photographer, to be able to go there. Because a journalist can get information from one side or another, create a system that will give the right information, but he doesn’t need to be there. A photographer, if he isn’t there, he doesn’t have the image; he has to go there. We expose ourselves a lot. So it’s an enormous privilege. And by walking through the exhibition, looking a bit, it’s amazing how I’ve travelled back in time through my life.

You’ve worked exclusively in black and white for decades. What draws you to this medium, and how does it shape the way you see and interpret the world?

Magazines in the ’70s and ’80s didn’t publish black-and-white photos. All the commissions were for colour, so I did a lot of colour photography. But never in my life was I a colour photographer. Colour bothered me enormously, making it hard to focus on the image. We used high-contrast slides at the time. If you have a blue hat or a red scarf, they become hugely important visually when I look at the final image, and it makes me lose all focus on your dignity and your personality. Black and white is an abstraction, as nothing is in black and white. I transformed all the ranges of colour into ranges of grey, where I could focus wherever I wanted and on the image reproduction that I wanted.

One of your most iconic series captured the oil fires set by the Iraqi military when it retreated from Kuwait in 1991 at the end of the Gulf War. What was it like covering such a dangerous situation?

I can’t hear you very well because I lost my hearing while working. It was when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and set fire to almost 600 oil wells. I was there to do a story for The New York Times for six months. Everyone was covering the war, but I wanted to cover the oil because it was so impressive. It was a terrible and sublime moment of my life. Terrible because it was the greatest pollution this planet has ever had. It was night 24 hours a day. And it was so stunning because at some point, there was a gust of wind that opened up the clouds and a ray of sunshine entered. It was like working in a theatre the size of the planet.

It was a privilege being there, in this light, with all these oil wells and all these people who were trying to stop the fires. It was very hard to approach a burning oil well because the temperature rose to more than 2,000 degrees centigrade. The sound of that oil well, the pressure coming out of the ground, was like working behind a jet turbine. And when I left Kuwait, I had already lost more than half of my hearing.

How did the idea come about for Instituto Terra, the environmental NGO that you and Lélia co- founded to restore the deteriorated landscapes of your birthplace in Brazil?

My parents made the decision to give their farm to us. Lélia said, “Sebastião, you’re not a farmer, nor am I. I’m a designer, an architect. You’re a photographer. We’re going to take this land and plant the forest that was here before.” So we started planting trees. And little by little, we started to rehabilitate the forest. We were not activists of any movement for the planet;

we simply wanted to plant a forest. At some point, we discovered that we were ecologists because everything we do is pure ecology. Today, we have planted 3,400,000 trees because we received a donation from Zurich Insurance Company, which gave us a lot of money to

buy land. Today, we have three times as many trees. We planted the entire space. It’s a magnificent forest. Now, we are starting to plant more. Possibly, in the next 10 years we will have planted at least 10 million more trees. It’s the largest ecological project in Brazil today.

Also see: